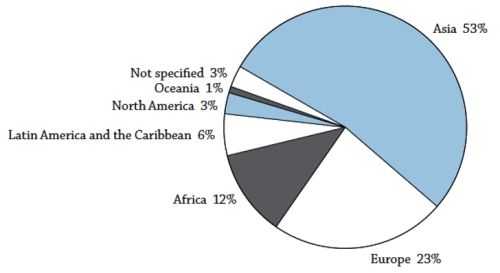

According to an OECD report from last year (but containing data upto 2012), “Asia is the source for more than half of today’s internationally mobile students (53%), with China, India, and South Korea the main source countries.” Even though the source countries for international higher education student mobilisation may remain the same in 2015, the distribution of higher education students to destination countries in numbers and percentages based on university and college admissions have changed.

In other words, student demand for international higher education is changing. Recent reports from the US and the UK suggest a serious decline in university admissions from international students – a trend visible from 2013. Australia, which had suffered a similar decline a couple of years ago, seems to have recovered by making conscious changes to their university admissions, visa and employment policies. The Australian government seems to have given its full support.

Image courtesy http://monitor.icef.com/

Although the US still remains the biggest attraction for students from China, India and other developing economies, followed by the UK (still an Indian favourite), countries such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand are showing increased eagerness to win over international students for their universities and colleges. Somewhat behind are countries like France, Germany, Sweden, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Singapore, Japan, and a few others. The federal governments of these countries are taking an active interest. Higher education is becoming an export sector for them. Hence, all these countries are stepping up their student recruitment efforts and channels.

They are building stronger relationships with developing economies and formulating their own national higher education strategies for international students. They are encouraging their universities and colleges to (a) develop courses and programmes which are more globally relevant, (b) set up student support services to ease student-university interactions, (c) reach out and market themselves to international students in their own countries and institutions, (d) recruit students through education and counselling agencies, (e) offer attractive scholarships, and (f) create multicultural student and social communities to welcome and engage international students.

And why not? The market for international higher education is quite substantial. In an article in Forbes magazine last month, titled How The U.S. Can Capture The $170B Opportunity In International Higher Education, Allison Williams (an Analyst at University Ventures), quoting Ryan Craig, author of College Disrupted: The Great Unbundling of Higher Education, writes:

Consider the following: Education is Australia’s largest services “export” sector, contributing $13.5 billion to the Australian economy, or roughly 1 percent of GDP… If the United States was able to generate 1 percent of GDP from the export of online programs, that’s $170 billion or about 7 times the current U.S. higher education “export market” (i.e., international students studying stateside). It would represent a 30 percent increase in the overall higher education market.

In theory, in a purely online world, the potential could be much larger than Australia’s 1 percent. American universities could compete with every Asian university for every Asian student—not simply for those willing to travel abroad. In practice, as average tuition per online student would be much lower than what Chinese students are paying today in Australia, 1 percent is a reasonable target and would make higher education America’s largest export, ahead of agriculture and entertainment.

[Citation: OECD releases detailed study of global education trends for 2014, OECD, 17 September 2014; How The U.S. Can Capture The $170B Opportunity In International Higher Education, Allison Williams, Forbes Magazine, July 21, 2015.]