Things are looking good for Australia’s higher education export sector. In the past two years, every year, close to 300,000 international students have enrolled into Australian universities and vocational education and training programmes. This puts Australia as one of the top four countries in international higher education – behind USA and the UK, but ahead of Canada.

The reason that attracts international students to these countries is primarily the superior quality of education offered by their universities. But, apart from the fact that these are all English-speaking countries (a factor that cannot be overlooked), another major reason is the attraction of being able to stay back in the destination country after graduation to find employment, permanent residence and citizenship.

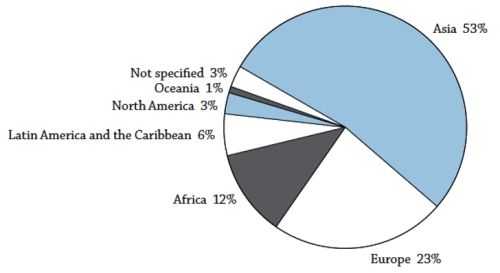

This second reason of employment, permanent residence and citizenship may offer fantastic opportunities to international students – most of whom come from higher-middle-income Asian and African families – but this regular influx of large numbers of international students can cause a dilemma for the governments of these destination countries. Australia, which receives hundreds of thousands of international students year after year, has been expressing aspects of this dilemma in the media recently.

Image courtesy http://www.studybrisbane.com.au

In a post earlier this month, we had talked about one such concern over housing and quoted from an article in The Age by Michael Pascoe. In that article, Mr Pascoe writes in separate instances,

“The reworked visa system is supposed to be tighter but still attractive to foreign students in what is a highly competitive international market for their custom.”

“The private education sector as well as public universities are actively hunting the fees.”

“Such strong growth also means further urgent need for investment in student housing. The RBA [Reserve Bank of Australia] submission observes that, as well as overall population growth, its composition influences housing demand.”

“So a rise in foreign student numbers should mean a rise in demand for rental accommodation in what already are housing hotspots.”

In another more recent online article, titled Is Australia hooked on international students? in Macrobusiness.com.au, Dr Jenny Stewart, Honorary Professor of Public Policy in the University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy, provides a detailed analysis of what this continuing growth in international students to Australia may mean to her country.

Here are selected excerpts from her article:

“The numbers are substantial. In 2013-2014, of just over 290,000 student visas that were granted, 153,000 were for study in higher education institutions. (Most of the rest were for vocational courses, which in turn offer a pathway towards onshore application for a higher education visa).”

“What do these undergraduate students do once they have completed their qualification? Many, understandably, wish to remain in Australia. Every year since 2006-2007 (the earliest year for which data at the relevant level of detail is readily available), the numbers of long-term arrivals in the higher education visa category have exceeded the numbers leaving by roughly 80,000 people per year.”

“Over the years, international students have brought a good deal of money to Australia and, each year, they continue to do so. Indeed the universities have become dependent upon them financially. The student-migrants are hard-working, and most get jobs.”

“But there are negative implications, too. Firstly, the need to attract, year in and year out, students in these kinds of numbers, has an impact on the prestige-value of Australian qualifications in the international market-place. This is because prestige is affected by the standards (including the English-language standards) that students must meet in order to graduate.”

“From a university perspective, it is enrolments that matter, so there is continuous pressure not to be too demanding when it comes to language skills, and if at all possible, to pass students as they undertake their degree-courses. (Similar factors operate in relation to domestic students).”

“If potential residency is part of the package, prestige may not matter so much to many students. But over time, we would expect it would become harder and harder to attract the best students from specific countries, as their own educational institutions mature, and ambitious families have more options to pursue.”

Dr Stewart gives us several critical pointers to how the higher education export sector may shape up for Australia in the years to come. We agree that the Australian government needs to address these concerns soon and adopt a long-term strategy towards Australia’s higher education exports, visa and immigration policies, housing, and the labour market.

You can read Dr Jenny Stewart’s entire article here.

[Citation: Foreign students set to power housing, Michael Pascoe, The Age, 4 August 2015; Is Australia hooked on international students?, Dr Jenny Stewart, Macrobusiness.com.au, 19 August 2015.]